Technique

Rear Window

The art of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 ‘masterpiece’ Rear Window

The Googled synopsis of this beguiling and landmark film reads as…

A professional photographer with a broken leg whiles away the time by spying on his neighbours through his window. However, his pastime becomes serious when he witnesses an apparent murder.

Well, yes, that is indeed the basic premise of a film that has become one of the most talked about and revered in cinematic history, some say it’s the greatest film ever made. Well, I don’t know about that, but you don’t have to wait too long, once you start watching it, to realise that there is so much more than just your edge-of-your-seat suspensefulness here, there are plot twists, … and a cinematic style that is jaw-droppingly gorgeous to behold.

Now, before I get carried away and go any further, I have one major reservation about Rear Window, and I’m sticking my neck out hugely here, but I think the ending is a bit of a stinker. Yup, I don’t think it works well. To me, the whole thing is rather rushed and improbable. It feels like they’d spent a huge amount of time and effort making everything so perfect up until the time that Lisa (Grace Kelly) breaks into Lars Thorwald’s (Raymond Burr) apartment, that they hadn’t really thought enough about how to end it. The film suddenly seems to run away with itself and the action and camera work becomes less controlled and it all feels a bit stagey, a bit farcical, a bit like bad theatre.

I’m probably going to be flamed for saying that but, hey, it’s just an opinion. For me, Rear Window isn’t the ‘greatest film ever made’, but boy, is it beautiful! There is so much in this 1 hour and 52 minutes that the budding director, cinematographer and set designer can learn from, that the film should be required study material for all film courses.

Let’s take a closer look at the key elements and techniques that make Rear Window the cinematic jewel that it is and how we can learn from them and adopt them for use in our own work.

Based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich, who was a writer known for steamy, suspenseful tales with chilling encounters set in the urban America of the 1930s and 40s. This adaptation of Rear Window set Hitchcock on the path to his other classics such as Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), and The Birds (1963).

The story of Rear Window is a simple one. A man, L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart) is laid up in his apartment having suffered a broken leg and spends his days watching his neighbours in the courtyard and through the windows of apartment block around him. For the most part, our viewpoint of the unfolding drama, comes through the prying eyes of Jefferies as he becomes increasingly captivated with the activities of those around him. Love, life and loneliness played out, as in a theatre, directly in front of him, his neighbours, seemingly unaware of his gaze.

However, right from the start, through the early scenes, it’s us, the viewer, who becomes equally as fascinated by the events on show. Each window we peer through, is like a film within a film and they all seem to display a different story. There is the newlyweds, with the bride being carried into the room; the young women dancer, who seems to be continuously rehearsing her moves as she goes about her daily routines; and the musician, who is struggling to finish his latest piece at the piano.

For Jefferies, however, the main attraction becomes a much darker one, when he suspects one of his neighbours, a salesman, has committed the murder of his wife and he begins to spy on him. Using a pair of binoculars he becomes obsessed with his every movement, tracking him day and night, as he moves mysteriously in and out of his apartment at all hours.

What we soon realise, watching the drama unfold, is that this has become a tale of peeping Toms. On the one hand, the central character, Jefferies, is guilty of peering into other people’s lives, but by extension, so are we, the audience, by staring at him. The underlying message is about a society living in fear of being watched but with an obsession of watching.

It’s a beautiful set and the design has added much to the claustrophobic mood of the film. As well as the walled in nature of the apartment block and courtyard, with only a glimpse of the outside world coming from a narrow passageway leading to the street, so too, the interior of Jefferies tiny apartment is made to feel cramped and confined.

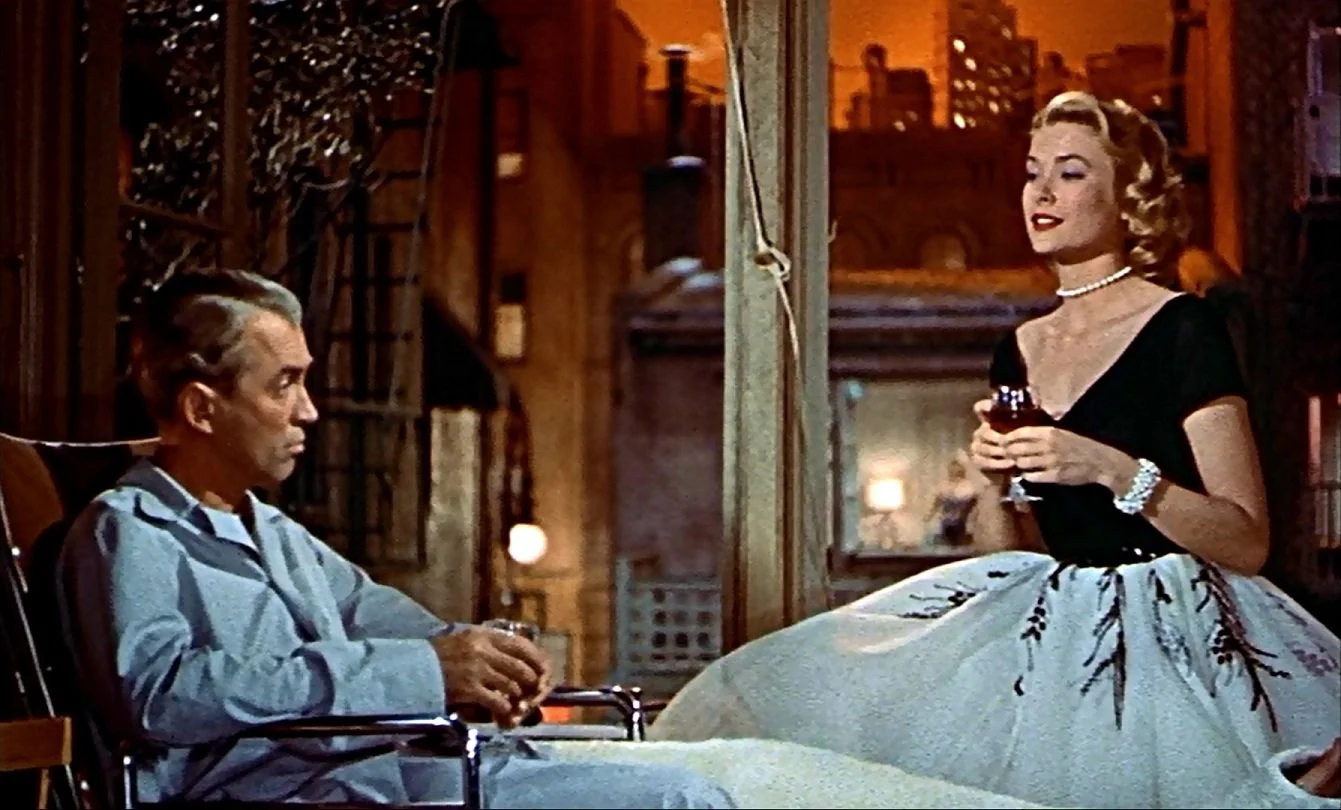

Sitting in his wheelchair, with his leg in a plaster cast and unable to move, he is a large presence in the room, taking up much of the space. The shelves and tables are crammed with stuff and along with the heatwave’s 90 degree temperatures, it feels stuffy and oppressive. This is a clever device and when another character enters the apartment, such as Grace Kelly in her elaborate gowns, the space fills up even more and the air seems thicker with tension.

There are very few camera angles, which again contributes to the enclosed and airless environment. There are a number of close-up shots keeping us at one with the mind of Jefferies and his growing obsession. Hitchcock was a master at using visual techniques such as these to engage the viewer and to draw us in to his world of intrigue and suspense.

And then there are the colours, oh my, the colours. The deep saturated reds and oranges; the stylish and crisp light blues and greens, they are all perfectly chosen to colour each scene in just the right way. The red lipstick that Grace Kelly wears pops to highten the mood whenever she appears. James Stewart’s crisp pyjamas add an air of dignity to his unfortunate situation. And even at night, as we peer out of his apartment window, the sky is one of a dramatic burnt orange, expectant and slightly menacing as the storm brews.

The colour palette is alluring but it provides a certain heaviness that feeds into the growing suspense of the film. We can admire its profound beauty but ultimately it feels like it’s painting the way for much more darkness to come.

Hitchcock went on to use similar techniques in films such

as Vertigo and North by Northwest, the set design and cinematography playing huge roles in creating mood and atmosphere.

The takeaway message from Rear Window and indeed all these films, is that the use of style, colour and location can play a very important part in conveying messages. When setting up a shot for either the moving or still image, careful consideration should made to the space being used and how it’s design and ambience can contribute to the mood of the scene.

If we consider our main subject and how we wish to portray them, their surroundings and environment should play an

integral role in conveying both their look and their character. Props, lighting and carefully considered framing are not only the basic building blocks of good composition but also the essential elements of successful image creation.

We will continue to look at this topic in later articles as we analyse composition, framing and style in both film and photography.

To read the rest of this article, please log-in to the Subscriber area of the site.

You can become a member, by following this link and setting up an account.

Recent blog post…

Street photography as cover art